|

| Contact: admin (a) blues-finland.com © 2008 Blues-Finland.com |

| Muddy Waters Part Two: Chicago Read also Part One & Part Three Says Muddy: "I was thinking to myself that I could do better in a big city. I thought I could make more money, and then I would have more opportunities to get into the big record field. /---/ I got here on a Saturday, got a job working at the paper factory, making containers. I was working Monday. /---/ Soon I put in some overtime, worked twelve hours a day and I brought a hundred and something bring-home pay. I said, 'Goodgodamighty, look at the money I got.' I have picked that cotton all the year, chop cotton all year, and I didn't draw a hundred dollars." |

|

| With Chicago still a "jazz town", there were few club dates available to blues players, with even well-established performers like Big Bill Broonzy and Memphis Slim only earning 6 dollars per person on a week night or 10 for a weekend date. Thus, Muddy started playing house parties instead, making 5 bucks a night, plus plenty of bootleg whiskey and fried chicken. Through his cousin, Muddy soon hooked up with his first band: guitarists Jimmy Rogers and Claude "Blue Smitty" Smith; whenever Smitty was around, Rogers would play the harmonica. Back at Stovall, Muddy had been told: "Naww, they don't listen to that kind of old blues you're doing now, don't nobody listen to that, not in Chicago." So as he started landing his first proper club gigs, his uncle Joe Grant went out and bought him an electric guitar. That Loud Sound "It wasn't no name-brand electric guitar, but it was a built-in electric guitar, not a pick-up just stuck on. It gave me so much trouble that that's probably why I forgot the name. Every time I looked around I had to have it fixed," Muddy reflected years later. "It was a very different sound, not just louder. I thought that I'd come to like it - if I could ever learn to play it. That loud sound would tell everything you were doing: on acoustic you could mess up a lot of stuff and no one would know that you'd ever missed." By the time Muddy started recording for the Aristocrat label, soon to become Chess Records, that troublesome guitar had been stolen and Muddy had replaced it with a Gretsch. Before the no-name electric his uncle got him had come the DeArmond pickup Jimmy Rogers used to amplify his acoustic with; Muddy also started using a thumbpick to further intensify his volume, and took lessons from Blue Smitty, who taught him to play in a more urban style: without a slide, and in standard tuning. The big break, however, came thanks to his grandmother, albeit by misfortune: Muddy was a beneficiary on Della's insurance, and when she passed away in 1946, he spent the money on a 2-door 1940 Chevy. Soon, he was playing with Eddie Boyd and Sunnyland Slim, and Sonny Boy Williamson I started hiring Muddy for gigs outside of Chicago. The way Jimmy Rogers put it, "blues players didn't have cars too much then." Mean Red Spider In 1946 came Muddy's first Chicago recordings; of the first session, produced by J. Mayo Williams in the "old" Chicago blues mold with clarinets and saxes, only "Mean Red Spider" was released, credited to James "Sweet Lucy" Carter, not Muddy Waters. Through that "indie" session, he met guitarist and drummer "Baby Face" Leroy Foster, and as Blue Smitty drifted off, that was the new band: Waters, Rogers, and Foster. The introduction of drums to their live act brought new popularity, and soon Muddy found himself in the studio again, this time for Columbia Records with the producer Lester Melrose, the creator of the pre-war "Bluebird sound". Muddy cut three tracks as a leader, another three backing vocalist Homer Harris, and two more with pianist Jimmy Clark. Only the Clark tracks were released at the time, again with no mention of Muddy Waters on the label. In 1947, Muddy's band became a quartet when Jimmy Rogers reeled in a wild teenage harmonica player from Maxwell Street, Marion "Little" Walter Jacobs. According to Muddy, "he wasn't drinking nothing but Pepsi-Cola, just a kid. /---/ The best harmonica player in the business." Notorious for their habit of showing up at other bands' gigs to "cut heads", the new line-up soon became known as the Headhunters - in Rogers' own words, "me and Muddy and Walter with a drum, we could sell just about anything." Can't Be Satisfied One afternoon, with Lonnie Johnson reluctantly lending him his guitar for an audition at the musicians' union hall, Muddy was "discovered" by Aristocrat label's African American talent scout Sammy Goldberg. His first session for the label came through Sunnyland Slim - in the wake of the success of Lightnin' Hopkins and John Lee Hooker, Aristocrat too was looking for smaller, more "cost-efficient" line-ups. Slim phoned Muddy, but he was out delivering Venetian blinds; a message was left for him at the office to go home and tend to his sick mother. Realizing that his mother had been dead a while, Muddy headed home, met Sunnyland, and hit the studio. "Gypsy Woman" and "Little Anna Mae" were released in February 1948, sounding nothing like Muddy's own band. In April, he recorded again with Sunnyland, insisting to try something "by himself" at the end of the session. With Ernest "Big" Crawford on bass, "I Be's Troubled" became "I Can't Be Satisfied", while the citified version of "Country Blues" was mistitled as "I Feel Like Going Home" - Muddy's actual line "feel like blowing my horn" signified a somewhat different intent. Leonard Chess was not sure he liked what he heard, but his Aristocrat partner Evelyn Aron was; the disc was released on a Friday and the first pressing was nearly gone by Saturday night. It would be another two years before Leonard would bring in his brother Phil, start Chess Records, and let Muddy use his full band in the studio - and before Muddy would finally quit his day job. Hoochie Coochie By 1950, blues gigs in Chicago were paying better than jazz gigs, so when Muddy needed a new drummer, Elga "Elgin" Edmonds stepped in, followed by other jazz drummers like Fred Below and Francis Clay. Otis Spann joined as a piano player in 1951, completing Muddy's classic line-up and unofficially taking over the everyday duties of running the band. When Little Walter got his solo hit with "Juke" and left, Junior Wells filled in, then James Cotton. Jimmy Rogers quit in 1956, briefly replaced by Hubert Sumlin. One night in the mensroom at Club Zanzibar, Willie Dixon taught Muddy the song "Hoochie Coochie Man"; soon after the record came out in 1954, Muddy bought his first house, moving in with his wife Geneva and her two kids. In 1955, Billboard Magazine wrote: "Only a few artists such as Muddy Waters, Dinah Washington, Memphis Slim, and B.B. King have what is known in pop stores as a standby market - that group which will buy an artist rather than the tune." As rock'n'roll stormed the charts, Muddy stopped playing guitar, leaving it to a pair of more "modern" guitarists in the band, and only appeared onstage to sing a few songs each set. Gigs were becoming scarce, and so was the pay, so in 1958, he accepted his first trip overseas, touring England with Otis Spann. Backed by jazz musicians better versed in Dixieland than blues, Muddy had no choice but to perform full-time and play guitar, and over there it was his own electric sound that shocked audiences as overly "modern", invoking headlines such as "Screaming Guitar and Howling Piano." In the US, Muddy first performance before a predominantly white audience came on July 3rd, 1960 at the Newport Jazz Festival, producing a Grammy-nominated live album. In the film footage of the gig, Muddy is seen brandishing the Fender Telecaster that was to become his trademark; on the cover of the album, he is depicted holding a big, old-fashioned hollowbody guitar, borrowed expressly for the photo from John Lee Hooker. The campaign to cross over to white folk and jazz audiences had begun. ANDRES ROOTS - - - - - The three-part Muddy Waters biography started with the episode "Mississippi" and concludes with the episode "Champagne & Reefer". In a poll arranged in the autumn of 2007, the readers of Blues-Finland.com voted Muddy the favourite blues artist of all time. |

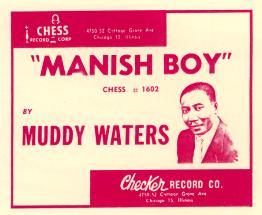

| Ad for Muddy's single "Mannish Boy". Note the spelling error. |